â€ëœcornelius Over and Over Again â€å“functional Redundancyã¢â‚¬â in the Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles[a] (Koinē Greek: Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, Práxeis Apostólōn;[2] Latin: Actūs Apostolōrum) is the 5th book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its bulletin to the Roman Empire.[3]

Acts and the Gospel of Luke make upward a two-part piece of work, Luke–Acts, by the same anonymous author.[four] Information technology is usually dated to around 80–90 Advertising, although some scholars advise 90–110. The commencement part, the Gospel of Luke, tells how God fulfilled his plan for the world's salvation through the life, expiry, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, the promised messiah. Acts continues the story of Christianity in the 1st century, beginning with the ascent of Jesus to Heaven. The early chapters, set in Jerusalem, describe the Day of Pentecost (the coming of the Holy Spirit) and the growth of the church building in Jerusalem. Initially, the Jews are receptive to the Christian message, just later they turn confronting the followers of Jesus. Rejected by the Jews, the message is taken to the Gentiles under the guidance of Paul the Apostle. The later capacity tell of Paul's conversion, his mission in Asia Minor and the Aegean, and finally his imprisonment in Rome, where, as the book ends, he awaits trial.

Luke–Acts is an attempt to answer a theological problem, namely how the Messiah of the Jews came to have an overwhelmingly not-Jewish church building; the answer it provides is that the message of Christ was sent to the Gentiles because the Jews rejected it.[3] Luke–Acts can as well exist seen as a defense of (or "apology" for) the Jesus movement addressed to the Jews: the majority of the speeches and sermons in Acts are addressed to Jewish audiences, with the Romans serving as external arbiters on disputes apropos Jewish community and law.[five] On the one mitt, Luke portrays the followers of Jesus as a sect of the Jews, and therefore entitled to legal protection equally a recognised faith; on the other, Luke seems unclear as to the futurity God intends for Jews and Christians, celebrating the Jewishness of Jesus and his immediate followers while also stressing how the Jews had rejected God'southward promised Messiah.[vi]

Limerick and setting [edit]

[edit]

The championship "Acts of the Apostles" was first used past Irenaeus in the late 2nd century. It is not known whether this was an existing title or one invented by Irenaeus; it does seem clear that it was not given past the writer, as the word práxeis (deeds, acts) only appears in one case in the text (Acts 19:xviii) and at that place it does not refer to the apostles only refers to deeds confessed past followers to the apostles.[2]

The Gospel of Luke and Acts make upwards a ii-volume work which scholars call Luke–Acts.[iv] Together they business relationship for 27.5% of the New Attestation, the largest contribution attributed to a single author, providing the framework for both the Church's liturgical agenda and the historical outline into which later generations have fitted their idea of the story of Jesus and the early church building.[7] The author is not named in either volume.[8] Co-ordinate to Church tradition dating from the second century, the author was the "Luke" named equally a companion of the apostle Paul in iii of the messages attributed to Paul himself; this view is still sometimes advanced, but "a critical consensus emphasizes the countless contradictions between the account in Acts and the authentic Pauline messages."[nine] (An example can be seen past comparing Acts'due south accounts of Paul's conversion (Acts nine:1–31, 22:half-dozen–21, and 26:ix–23) with Paul'south ain statement that he remained unknown to Christians in Judea after that effect (Galatians 1:17–24).)[ten] The author "is an admirer of Paul, but does not share Paul'southward own view of himself every bit an apostle; his own theology is considerably different from Paul'southward on fundamental points and does non represent Paul's own views accurately."[xi] He was educated, a man of means, probably urban, and someone who respected manual work, although not a worker himself; this is significant, because more high-brow writers of the time looked down on the artisans and small business organisation people who made up the early on church of Paul and were presumably Luke's audience.[12]

The earliest possible date for Luke-Acts is around 62 Advertizing,[ citation needed ] the time of Paul's imprisonment in Rome, just nigh scholars date the work to 80–90 Advertising on the grounds that it uses Marker as a source, looks back on the destruction of Jerusalem, and does not show any sensation of the letters of Paul (which began circulating late in the first century); if it does prove sensation of the Pauline epistles, and also of the work of the Jewish historian Josephus, as some believe, then a date in the early 2nd century is possible.[13]

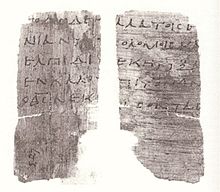

Manuscripts [edit]

At that place are ii major textual variants of Acts, the Western text-type and the Alexandrian. The oldest complete Alexandrian manuscripts date from the 4th century and the oldest Western ones from the 6th, with fragments and citations going dorsum to the third. Western texts of Acts are 6.2–8.4% longer than Alexandrian texts, the additions tending to enhance the Jewish rejection of the Messiah and the function of the Holy Spirit, in means that are stylistically dissimilar from the residuum of Acts.[xiv] The majority of scholars prefer the Alexandrian (shorter) text-type over the Western every bit the more authentic, but this same argument would favour the Western over the Alexandrian for the Gospel of Luke, as in that instance the Western version is the shorter.[14]

Genre, sources and historicity of Acts [edit]

The title "Acts of the Apostles" (Praxeis Apostolon) would seem to place information technology with the genre telling of the deeds and achievements of peachy men (praxeis), but it was not the championship given past the author.[two] The anonymous writer aligned Luke–Acts to the "narratives" (διήγησις, diēgēsis) which many others had written, and described his own work as an "orderly account" (ἀκριβῶς καθεξῆς). It lacks exact analogies in Hellenistic or Jewish literature.[15]

The author may have taken as his model the works of Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who wrote a well-known history of Rome, or the Jewish historian Josephus, writer of a history of the Jews.[16] Like them, he anchors his history by dating the birth of the founder (Romulus for Dionysius, Moses for Josephus, Jesus for Luke) and similar them he tells how the founder is born from God, taught authoritatively, and appeared to witnesses afterward death earlier ascending to heaven.[sixteen] Generally the sources for Acts tin merely be guessed at,[17] but the author would have had access to the Septuagint (a Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures), the Gospel of Mark, and either the hypothetical drove of "sayings of Jesus" chosen the Q source or the Gospel of Matthew.[18] [xix] He transposed a few incidents from Mark's gospel to the time of the Apostles—for example, the material about "make clean" and "unclean" foods in Mark vii is used in Acts x, and Mark'due south account of the accusation that Jesus has attacked the Temple (Marking 14:58) is used in a story about Stephen (Acts half-dozen:14).[20] At that place are also points of contacts (significant suggestive parallels but something less than articulate testify) with 1 Peter, the Letter of the alphabet to the Hebrews, and 1 Cloudless.[21] [22] Other sources can merely be inferred from internal evidence—the traditional explanation of the iii "we" passages, for instance, is that they correspond eyewitness accounts.[23] The search for such inferred sources was popular in the 19th century, but by the mid-20th it had largely been abased.[24]

Acts was read every bit a reliable history of the early church well into the mail service-Reformation era, but by the 17th century biblical scholars began to notice that information technology was incomplete and tendentious—its picture of a harmonious church building is quite at odds with that given past Paul'southward messages, and information technology omits important events such equally the deaths of both Peter and Paul. The mid-19th-century scholar Ferdinand Baur suggested that the author had re-written history to present a united Peter and Paul and advance a single orthodoxy against the Marcionites (Marcion was a 2d-century heretic who wished to cutting Christianity off entirely from the Jews); Baur continues to accept enormous influence, but today there is less interest in determining the historical accuracy of Acts (although this has never died out) than in understanding the author'southward theological program.[25]

Audience and authorial intent [edit]

Luke was written to exist read aloud to a group of Jesus-followers gathered in a house to share the Lord's supper.[16] The author assumes an educated Greek-speaking audition, but directs his attention to specifically Christian concerns rather than to the Greco-Roman earth at large.[26] He begins his gospel with a preface addressed to Theophilus (Luke 1:3; cf. Acts 1:1), informing him of his intention to provide an "ordered account" of events which will lead his reader to "certainty".[12] He did not write in order to provide Theophilus with historical justification—"did information technology happen?"—but to encourage faith—"what happened, and what does it all mean?"[27]

Acts (or Luke–Acts) is intended as a work of "betterment," pregnant "the empirical sit-in that virtue is superior to vice."[28] [29] The work also engages with the question of a Christian's proper human relationship with the Roman Empire, the ceremonious power of the day: could a Christian obey God and too Caesar? The answer is ambiguous.[5] The Romans never move against Jesus or his followers unless provoked by the Jews, in the trial scenes the Christian missionaries are always cleared of charges of violating Roman laws, and Acts ends with Paul in Rome proclaiming the Christian message under Roman protection; at the aforementioned time, Luke makes articulate that the Romans, like all earthly rulers, receive their authorization from Satan, while Christ is ruler of the kingdom of God.[30]

Structure and content [edit]

Construction [edit]

Acts has two key structural principles. The offset is the geographic movement from Jerusalem, centre of God's Covenantal people, the Jews, to Rome, heart of the Gentile world. This structure reaches dorsum to the author's preceding work, the Gospel of Luke, and is signaled by parallel scenes such equally Paul's utterance in Acts 19:21, which echoes Jesus's words in Luke 9:51: Paul has Rome as his destination, every bit Jesus had Jerusalem. The second primal element is the roles of Peter and Paul, the first representing the Jewish Christian church, the second the mission to the Gentiles.[31]

- Transition: reprise of the preface addressed to Theophilus and the closing events of the gospel (Acts i–1:26)

- Petrine Christianity: the Jewish church from Jerusalem to Antioch (Acts 2:1–12:25)

-

- 2:one–viii:1 – beginnings in Jerusalem

- 8:2–xl – the church expands to Samaria and beyond

- 9:1–31 – conversion of Paul

- 9:32–12:25 – the conversion of Cornelius, and the formation of the Antioch church

- Pauline Christianity: the Gentile mission from Antioch to Rome (Acts 13:1–28:31)

-

- 13:1–14:28 – the Gentile mission is promoted from Antioch

- fifteen:1–35 – the Gentile mission is confirmed in Jerusalem

- xv:36–28:31 – the Gentile mission, climaxing in Paul's passion story in Rome (21:17–28:31)

Outline [edit]

- Dedication to Theophilus (1:1–2)

- Resurrection appearances (one:iii)

- Great Commission (1:4–eight)

- Ascension (i:ix)

- Second Coming Prophecy (1:ten–11)

- Matthias replaced Judas (1:12–26)

- the Upper Room (one:13)

- The Holy Spirit came at Shavuot (Pentecost) (two:one-47), meet also Paraclete

- Peter healed a crippled beggar (3:1–10)

- Peter's spoken language at the Temple (3:11–26)

- Peter and John before the Sanhedrin (4:1–22)

- Resurrection of the dead (iv:2)

- Believers' Prayer (4:23–31)

- Everything is shared (4:32–37)

- Ananias and Sapphira (five:1–eleven)

- Signs and Wonders (5:12–xvi)

- Apostles earlier the Sanhedrin (5:17–42)

- 7 Deacons appointed (6:1–seven)

- Stephen before the Sanhedrin (6:8–7:60)

- The "Cave of the Patriarchs" was located in Shechem (7:xvi)

- "Moses was educated in all the wisdom of the Egyptians" (vii:22)

- First mentioning of Saul (Paul the Apostle) in the Bible (7:58)

- Paul the Campaigner confesses his function in the martyrdom of Stephen (7:58–60)

- Saul persecuted the Church of Jerusalem (8:1–iii)

- Philip the Evangelist (viii:iv–forty)

- Simon Magus (8:ix–24)

- Ethiopian eunuch (8:26–39)

- Conversion of Paul the Apostle (ix:1–31, 22:1–22, 26:9–24)

- Paul the Apostle confesses his active part in the martyrdom of Stephen (22:20)

- Peter healed Aeneas and raised Tabitha from the expressionless (9:32–43)

- Conversion of Cornelius (ten:1–eight, 24–48)

- Peter'south vision of a sheet with animals (10:ix–23, 11:i–18)

- Church building of Antioch founded (11:19–thirty)

- term "Christian" start used (xi:26)

- James the Great executed (12:1–2)

- Peter's rescue from prison (12:3–19)

- Death of Herod Agrippa I [in 44] (12:twenty–25)

- "the voice of a god" (12:22)

- Mission of Barnabas and Saul (xiii–14)

- "Saul, who was too known every bit Paul" (thirteen:nine)

- called "gods ... in man grade" (xiv:11)

- Quango of Jerusalem (15:1–35)

- Paul separated from Barnabas (15:36–41)

- 2nd and 3rd missions (16–twenty)

- Areopagus sermon (17:16–34)

- "God...has gear up a twenty-four hour period" (17:30–31)

- Trial earlier Gallio c. 51–52 (xviii:12–17)

- Areopagus sermon (17:16–34)

- Trip to Jerusalem (21)

- Before the people and the Sanhedrin (22–23)

- Before Felix–Festus–Herod Agrippa 2 (24–26)

- Trip to Rome (27–28)

- called a god on Malta (28:6)

Content [edit]

The Gospel of Luke began with a prologue addressed to Theophilus; Acts likewise opens with an address to Theophilus and refers to "my before book", most certainly the gospel.

The apostles and other followers of Jesus encounter and elect Matthias to replace Judas as a member of The Twelve. On Pentecost, the Holy Spirit descends and confers God's power on them, and Peter and John preach to many in Jerusalem and perform healings, casting out of evil spirits, and raising of the dead. The showtime believers share all holding in common, eat in each other'south homes, and worship together. At start many Jews follow Christ and are baptized, but the followers of Jesus begin to be increasingly persecuted by other Jews. Stephen is accused of blasphemy and stoned. Stephen's death marks a major turning point: the Jews have rejected the message, and henceforth it volition be taken to the Gentiles.[32]

The death of Stephen initiates persecution, and many followers of Jesus go out Jerusalem. The message is taken to the Samaritans, a people rejected by Jews, and to the Gentiles. Saul of Tarsus, 1 of the Jews who persecuted the followers of Jesus, is converted by a vision to get a follower of Christ (an event which Luke regards as so important that he relates it iii times). Peter, directed past a series of visions, preaches to Cornelius the Centurion, a Gentile God-fearer, who becomes a follower of Christ. The Holy Spirit descends on Cornelius and his guests, thus confirming that the message of eternal life in Christ is for all mankind. The Gentile church is established in Antioch (n-western Syria, the third-largest city of the empire), and here Christ's followers are first chosen Christians.[33]

The mission to the Gentiles is promoted from Antioch and confirmed at a meeting in Jerusalem between Paul and the leadership of the Jerusalem church. Paul spends the next few years traveling through western asia Minor and the Aegean, preaching, converting, and founding new churches. On a visit to Jerusalem he is set on by a Jewish mob. Saved by the Roman commander, he is accused by the Jews of being a revolutionary, the "ringleader of the sect of the Nazarenes", and imprisoned. Later, Paul asserts his right as a Roman citizen, to be tried in Rome and is sent by sea to Rome, where he spends some other ii years under house arrest, proclaiming the Kingdom of God and teaching freely virtually "the Lord Jesus Christ". Acts ends abruptly without recording the outcome of Paul's legal troubles.[34]

Theology [edit]

Prior to the 1950s, Luke–Acts was seen as a historical piece of work, written to defend Christianity earlier the Romans or Paul confronting his detractors; since then the trend has been to see the piece of work every bit primarily theological.[35] Luke's theology is expressed primarily through his overarching plot, the style scenes, themes and characters combine to construct his specific worldview.[36] His "salvation history" stretches from the Creation to the present time of his readers, in iii ages: first, the time of "the Police and the Prophets" (Luke 16:16), the menses beginning with Genesis and ending with the appearance of John the Baptist (Luke 1:5–iii:1); second, the epoch of Jesus, in which the Kingdom of God was preached (Luke 3:2–24:51); and finally the catamenia of the Church building, which began when the risen Christ was taken into Heaven, and would finish with his second coming.[37]

Luke–Acts is an effort to respond a theological problem, namely how the Messiah, promised to the Jews, came to take an overwhelmingly non-Jewish church building; the answer it provides, and its key theme, is that the message of Christ was sent to the Gentiles because the Jews rejected information technology.[3] This theme is introduced in Chapter 4 of the Gospel of Luke, when Jesus, rejected in Nazareth, recalls that the prophets were rejected by State of israel and accepted past Gentiles; at the finish of the gospel he commands his disciples to preach his message to all nations, "beginning from Jerusalem." He repeats the command in Acts, telling them to preach "in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the cease of the Earth." They then continue to exercise and then, in the order outlined: first Jerusalem, so Judea and Samaria, and so the entire (Roman) world.[38]

For Luke, the Holy Spirit is the driving force behind the spread of the Christian message, and he places more accent on it than do whatever of the other evangelists. The Spirit is "poured out" at Pentecost on the outset Samaritan and Gentile believers and on disciples who had been baptised only by John the Baptist, each time every bit a sign of God'southward blessing. The Holy Spirit represents God's power (at his ascension, Jesus tells his followers, "You shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you"): through it the disciples are given oral communication to convert thousands in Jerusalem, forming the first church (the term is used for the commencement time in Acts 5).[39]

One consequence debated by scholars is Luke's political vision regarding the relationship betwixt the early church and the Roman Empire. On the one hand, Luke generally does not portray this interaction as one of direct conflict. Rather, there are ways in which each may have considered having a relationship with the other rather advantageous to its ain cause. For example, early on Christians may have appreciated hearing most the protection Paul received from Roman officials confronting Gentile rioters in Philippi (Acts 16:16–40) and Ephesus (Acts 19:23–41), and against Jewish rioters on two occasions (Acts 17:1–17; Acts xviii:12–17). Meanwhile, Roman readers may have canonical of Paul'due south censure of the illegal practice of magic (Acts nineteen:17–nineteen) too as the amicability of his rapport with Roman officials such as Sergius Paulus (Acts 13:half dozen–12) and Festus (Acts 26:30–32). Furthermore, Acts does not include any account of a struggle between Christians and the Roman authorities as a event of the latter's majestic cult. Thus Paul is depicted as a moderating presence between the church and the Roman Empire.[40]

On the other manus, events such equally the imprisonment of Paul at the easily of the empire (Acts 22–28) as well equally several encounters that reflect negatively on Roman officials (for instance, Felix's desire for a bribe from Paul in Acts 24:26) office as concrete points of conflict between Rome and the early on church.[41] Perhaps the about significant point of tension betwixt Roman imperial ideology and Luke'due south political vision is reflected in Peter'southward speech communication to the Roman centurion, Cornelius (Acts 10:36). Peter states that "this ane" [οὗτος], i.east. Jesus, "is lord [κύριος] of all." The championship, κύριος, was often ascribed to the Roman emperor in antiquity, rendering its use by Luke as an appellation for Jesus an unsubtle challenge to the emperor'south authority.[42]

Comparison with other writings [edit]

Gospel of Luke [edit]

As the 2d role of the two-role work Luke–Acts, Acts has significant links to the Gospel of Luke. Major turning points in the structure of Acts, for example, find parallels in Luke: the presentation of the child Jesus in the Temple parallels the opening of Acts in the Temple, Jesus's forty days of testing in the wilderness prior to his mission parallel the 40 days prior to his Rise in Acts, the mission of Jesus in Samaria and the Decapolis (the lands of the Samaritans and Gentiles) parallels the missions of the Apostles in Samaria and the Gentile lands, and then on (see Gospel of Luke). These parallels continue through both books. At that place are also differences between Luke and Acts, amounting at times to outright contradiction. For example, the gospel seems to place the Ascension on Easter Sunday, immediately after the Resurrection, while Acts 1 puts it forty days later.[43] There are similar conflicts over the theology, and while not seriously questioning the single authorship of Luke–Acts, these differences do advise the need for caution in seeking likewise much consistency in books written in essence as popular literature.[44]

Pauline epistles [edit]

Acts agrees with Paul's letters on the major outline of Paul's career: he is converted and becomes a Christian missionary and campaigner, establishing new churches in Asia Small and the Aegean and struggling to free Gentile Christians from the Jewish Law. At that place are also agreements on many incidents, such as Paul's escape from Damascus, where he is lowered downwards the walls in a basket. But details of these same incidents are often contradictory: for example, co-ordinate to Paul it was a infidel king who was trying to arrest him in Damascus, simply co-ordinate to Luke it was the Jews (ii Corinthians 11:33 and Acts ix:24). Acts speaks of "Christians" and "disciples", simply Paul never uses either term, and information technology is striking that Acts never brings Paul into conflict with the Jerusalem church and places Paul under the potency of the Jerusalem church and its leaders, particularly James and Peter (Acts 15 vs. Galatians ii).[45] Acts omits much from the letters, notably Paul's problems with his congregations (internal difficulties are said to be the error of the Jews instead), and his apparent final rejection by the church leaders in Jerusalem (Acts has Paul and Barnabas deliver an offering that is accepted, a trip that has no mention in the letters). There are also major differences between Acts and Paul on Christology (the understanding of Christ's nature), eschatology (the understanding of the "last things"), and apostleship.[46]

Run across also [edit]

- Les Actes des Apotres

- Acts of the Apostles (genre)

- Historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles

- Holy Spirit in the Acts of the Apostles

- List of Gospels

- List of New Testament verses not included in modernistic English translations

- The Lost Chapter of the Acts of the Apostles, also known as the Sonnini Manuscript

- Textual variants in the Acts of the Apostles

Notes [edit]

- ^ The volume is sometimes simply chosen Acts (which is also its nigh mutual grade of abbreviation).[ane]

References [edit]

- ^ "Bible Volume Abbreviations". Logos Bible Software. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c Matthews 2011, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Burkett 2002, p. 263.

- ^ a b Burkett 2002, p. 195.

- ^ a b Pickett 2011, pp. half-dozen–7.

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 563.

- ^ Slow 2012, p. 556.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 196.

- ^ Theissen & Merz 1998, p. 32.

- ^ Perkins 1998, p. 253.

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 590.

- ^ a b Dark-green 1997, p. 35.

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 587.

- ^ a b Thompson 2010, p. 332.

- ^ Aune 1988, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Balch 2003, p. 1104.

- ^ Bruce 1990, p. xl.

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 577.

- ^ Powell 2018, p. 113.

- ^ Witherington 1998, p. 8.

- ^ Tiresome 2012, p. 578.

- ^ Pierson Parker. (1965). The "Former Treatise" and the Engagement of Acts. Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 84, No. ane (Mar., 1965), pp. 52-58 (7 pages). "Furthermore, the relative calm of both of Luke'due south books, and sparse apocalyptic every bit compared with Matthew and Mark, sugg the church building was out from under duress when Luke wrote. This is cially true of Acts. Some scholars used to put Acts in the second century, but few present would do then. Indeed if Cloudless of Rom knew the book, as he seems to have washed, information technology volition have to be prior to a. d. 96." and "I Clem 2 1 with Acts 20 35; I Clem 5 4 with Acts 12 17; I Clem eighteen 1 w 13 22; I Clem 41 1 with Acts 23 i; I Clem 42 one-4, 44 ii with Acts 1-eight; I Clem with Acts 26 7; I Clem 59 2."

- ^ Bruce 1990, pp. xl–41.

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 579.

- ^ Holladay 2011, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Dark-green 1995, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Light-green 1997, p. 36.

- ^ Fitzmyer 1998, pp. 55–65.

- ^ Aune 1988, p. eighty.

- ^ Wearisome 2012, p. 562.

- ^ Wearisome 2012, pp. 569–70.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 265.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 266.

- ^ Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible . Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C.; Beck, Astrid B. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans. 2000. ISBN978-0-8028-2400-four. OCLC 44454699.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Buckwalter 1996, p. 6.

- ^ Allen 2009, p. 326.

- ^ Evans 2011, p. no page numbers.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 264.

- ^ Burkett 2002, pp. 268–70.

- ^ Phillips 2009, p. 119.

- ^ Phillips 2009, pp. 119–21.

- ^ Rowe 2005, pp. 291–98.

- ^ Zwiep 2010, p. 39.

- ^ Parsons 1993, pp. 17–eighteen.

- ^ Phillips, Thomas E. (January 1, 2010). Paul, His Letters, and Acts. One thousand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Bookish. p. 196. ISBN978-1-4412-5793-ii.

- ^ Boring 2012, pp. 581, 588–xc.

Bibliography [edit]

- Allen, O. Wesley, Jr. (2009). "Luke". In Petersen, David Fifty.; O'Day, Gail R. (eds.). Theological Bible Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN978-1-61164-030-4.

- Aune, David E. (1988). The New Testament in its Literary Surroundings. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN978-0-227-67910-iv.

- Balch, David L. (2003). "Luke". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN978-0-8028-3711-0.

- Deadening, K. Eugene (2012). An Introduction to the New Testament: History, Literature, Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN978-0-664-25592-3.

- Bruce, F.F. (1990). The Acts of the Apostles: The Greek Text with Introduction and Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN978-0-8028-0966-7.

- Buckwalter, Douglas (1996). The Graphic symbol and Purpose of Luke's Christology. Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-0-521-56180-8.

- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An Introduction to the New Attestation and the Origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-0-521-00720-7.

- Charlesworth, James H. (2008). The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon Printing. ISBN978-ane-4267-2475-half-dozen.

- Evans, Craig A. (2011). Luke. Baker Books. ISBN978-one-4412-3652-4.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (1998). The Anchor Bible: The Acts of the Apostles-A new Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Doubleday. ISBN978-0-385-49020-7.

- Gooding, David (2013). True to the Religion: The Acts of the Apostles: Defining and Defending the Gospel. Myrtlefield House. ISBN978-1-874584-31-five.

- Green, Joel (1995). The Theology of the Gospel of Luke. Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN978-0521469326.

- Green, Joel (1997). The Gospel of Luke. Eerdmans. ISBN9780802823151.

- Holladay, Carl R. (2011). A Disquisitional Introduction to the New Testament: Interpreting the Message and Pregnant of Jesus Christ. Abingdon Press. ISBN9781426748288.

- Keener, Craig S. (2012). Acts: An Exegetical Commentary. Vol. I: Introduction And 1:1–2:47. Baker Academic. ISBN978-1-4412-3621-0.

- Marshall, I. Howard (2014). Tyndale New Attestation Commentary: Acts. InterVarsity Printing. ISBN9780830898312.

- Matthews, Christopher R. (2011). "Acts of the Apostles". In Coogan, Michael D. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Books of the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN9780195377378.

- Parsons, Mikeal C. (1993). Rethinking the Unity of Luke and Acts. Fortress Press. ISBN978-1-4514-1701-2.

- Perkins, Pheme (1998). "The Synoptic Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles: Telling the Christian Story". In Barton, John (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Biblical Interpretation. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN978-0-521-48593-7.

- Phillips, Thomas Due east. (2009). Paul, His Letters, and Acts. Baker Academic. ISBN978-1-4412-4194-8.

- Pickett, Raymond (2011). "Luke and Empire: An Introduction". In Rhoads, David; Esterline, David; Lee, Jae Won (eds.). Luke–Acts and Empire: Essays in Honor of Robert L. Brawley. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN9781608990986.

- Powell, Mark Allan (2018). Introducing the New Testament: A Historical, Literary and Theological Survey (2nd ed.). Baker Bookish. ISBN978-1-4934-1313-3.

- Rowe, C. Kavin (2005). "Luke–Acts and the Imperial Cult: A Mode through the Conundrum?". Journal for the Study of the New Attestation. 27 (3): 279–300. doi:10.1177/0142064X05052507. S2CID 162896700.

- Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1998). The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Eerdmans.

- Thompson, Richard P. (2010). "Luke-Acts: The Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles". In Aune, David East. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to The New Testament. Wiley–Blackwell. ISBN978-1-4443-1894-4.

- Witherington, Ben (1998). The Acts of the Apostles: A Socio-rhetorical Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN978-0-8028-4501-half dozen.

- Zwiep, Arie Due west. (2010). Christ, the Spirit and the Customs of God: Essays on the Acts of the Apostles. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN978-3-16-150675-8.

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acts_of_the_Apostles

0 Response to "â€ëœcornelius Over and Over Again â€å“functional Redundancyã¢â‚¬â in the Acts of the Apostles"

Post a Comment